[English version of Travailler avec les Français: témoignages de 22 étrangers de 19 pays]

Recurring topics

After a first collection of experience feedback from foreigners who have or have had professional interactions with the French published online at the end of August (see here), here is a second series produced by a second class of the MBA Cybersecurity Management and Information Systems Governance (MACYB) of the Economic Warfare School (EGE) where I have been teaching intercultural risk management for almost fifteen years.

The students were very engaged and conducted more than twenty interviews, each one more exciting than the last (congratulations to them!). They then had to transcribe them, identify recurring topics and draw lessons for cooperation. As with the first class, the aim of this unusual exercise was to take them out of their usual cultural references and to collect the experiences of foreigners with the French. This time, the goal is to go beyond stereotypes, to identify trends and frequencies of certain phenomena, and to develop international effectiveness.

If you compare this new series with the previous one, you will notice how much the foreigners’ feedback echoes each other to give a very similar picture of their relations with the French: the contradiction between freedom of expression and its limitation imposed by hierarchical distance, the theoretical dimension of reasoning style that produces excellent pedagogues but also excessively argumentative people, the mystery of long and not very productive meetings combined with an undeniable professional efficiency, the difficulty of giving constructive feedback, the key value of politeness, the ability to enjoy life outside of the professional life, the reluctance to recognize the value of “others”, especially foreigners.

Every cultural context has strengths and weaknesses for cooperation. If interviews were conducted with foreigners working with Germans or Americans, we would have a different picture, with different challenges and opportunities. I can only encourage everyone to get into the habit of collecting this valuable feedback, which has the double benefit of allowing us to go beyond stereotypes and adding an empirical dimension to the concepts of the intercultural approach.

For ease of reading, the excerpts are divided into eight sections:

- Hierarchical relationships

- Feedback

- Meetings

- Communication

- Explain, argue, convince

- Work/life balance

- Interpersonal relationships

- Barriers, challenges, and glass ceilings

NB: First names have been changed and any element allowing identification of the persons or their companies has been removed. The comments in italics, the images or videos at the end of each section are mine.

1. Hierarchical relationships

Assane (Senegalese): In the professional environment, communication is clear, targeted, the message gets through. But in general, I noticed that communication is very hierarchical: the big boss never talks to us directly, but always goes through the deputy boss, who talks to the lower level, etc. When we talk about communication between individuals, we can say that they are a bit too reserved. Overall, there is not much exchange at work, except when there is a little affinity.

Paloma (Brazilian): Regarding the relationship with the hierarchy, with the introduction of tutoiement [informal way of addressing someone in French] there was an impression of closeness, while it was a trap for all those who did not have the intelligence to respect the hierarchy. This hypocrisy is aggravated by the fact that they daily criticize their professional context, including their superiors, without ever complaining or arguing with them.

Jakub (Polish): I perceive the French work culture as a very hierarchical model. I think in Poland it is easier to criticize your superiors, easier to criticize ideas that come from above. I had my own team of French people and I struggled for a long time to get them to question my ideas and to have a critical approach to the concepts that other managers brought to the discussion. And it wasn’t because they didn’t have the skills. People are very competent and very well educated, but I think they feel they shouldn’t be criticizing or challenging anything from the top. My supervisors often wanted to know what I was doing and who I was meeting with, and they wanted to control who I was talking to and who I wasn’t.

Mithil (Indian, works in France and the Netherlands): In France the hierarchy is very strong. But in Holland the hierarchy is not very strong. In France, I can’t implement my idea without talking to my manager. So I have to talk to my manager. If he says it’s good, that it’s right, then I can express it. But in the Netherlands, if it’s just a little idea, I’m free to do it. Also, they like it when you challenge them. I can tell my director that what he said is not right. It’s not frowned upon. But in France we don’t have that much freedom.

Julian (Canadian): In America, we don’t distinguish between the boss and the subordinate. There is no complex between the supervisor and the non-supervisor. It’s a team effort, which means that if the supervisor has to deal with something he doesn’t know, he’s able to defer to the subordinate to learn. There is no such complex. In the French, a person who is a superior wants to be right, to be the one who knows everything. As a rule, the superior is not able to clearly accept the remarks of his or her subordinates.

Let’s take the example of seminars or team training in companies. The whole staff must participate, including the boss, who is not exempt. During a seminar in Canada, if the boss did not do a certain exercise well, the results of the whole team are made public, including the boss, so there is no shame or prohibition to say that the boss made a mistake. If there is a recommendation to be made, the same recommendation made to the subordinate would also apply to the leader. Our philosophy is that if the subordinate is absent from his post, the leader must be able to work in his place.

Lucas (Belgium): When discussing or exchanging ideas in a meeting to make a decision, the French sometimes need a manager’s approval, and sometimes decisions are made quickly because of seniority.

Elena (Romanian): When a top manager arrives, he or she is accompanied by a more senior manager who introduces him or her to the team. We are prepared and informed when it happens. From the first day, I noticed their great courtesy, all the time. At first they seem friendly, sympathetic, gallant, but at the same time they are a bit distant. You can feel a distance imposed by the hierarchical position, of course, but the French also impose this distance by their good manners, very visible, I would say. They never show that they are hostile or angry, they have this distant benevolence.

Heather (American): When a French person says to you: “This situation is not ideal, we’re asking for your recommendations,” they’re not really taking them into account. There is a problem of sharing. Because of the strong hierarchy, certain things should not happen at certain levels. In France, we prioritize access to information, even if it’s not necessary. For example, certain business decisions require knowledge of several factors in order to react. But because information doesn’t circulate well upstream, you don’t necessarily explain why decisions are made. And that’s a real French problem.

Moussa (Senegalese): In general, managers, if an idea doesn’t come from them, they are very reluctant to accept it, they don’t see the potential of the idea you bring. It’s like they don’t even try to understand.

Jakub (Polish): It seems that education in France is very good for technical skills, maybe for working in small groups, but there is no good education for managing people and teams. Managers want the team to reflect their idea, which is a big pitfall in thinking. It’s not only in France, but in France I’ve seen very often that people want their ideas to be realized by the team, not the team’s ideas to be accepted.

Ahouéfa (Beninese): French management is very hierarchical. I see it in the company where I work. We have N+7 and that doesn’t exist in other countries, such a strong and deep-rooted hierarchy. And as a result, we tend to fear the N+4 to the point that sometimes when he comes, we have to get up, clean the offices, etc. I would say that this is a model of the old monarchy, and I would say that this is perhaps normal with the history of France.

Liam (Canadian): The hierarchical organization chart has a central value in French style management, the CEO or director is addressed as “vous” [formal way of addressing someone in French], the subordinate management relationship is very strong in France compared to other countries in the world where you could address all your colleagues as “tu” [informal way of addressing someone in French], including the CEO.

Heather (American): In the Netherlands, no one is surprised when a project manager sends an email directly to the CEO with his manager as a copy to share information. I’ll let you imagine such a situation in France. It could be perceived as bypassing the hierarchy. The Dutch don’t have a problem with knowledge coming from a lower level of the hierarchy without coming from the boss. It is just that the information transferred must be adapted and relevant to the recipient.

Ahouéfa (Beninese): For me, the French are of course very professional, but they are also very attached to personality, proximity and affinity. I have noticed that for a woman, the person has to be very intelligent, for a man a little less, but also that the person has to be friendly, submissive and close to the management. I wouldn’t say sycophantic, we shouldn’t exaggerate either, but the person has to be in the bosses’ good books. I have seen that French managers think of the person they see a lot in meetings, the one who talks a lot, the one who shouts the loudest, but not necessarily the most competent.

Carla (Italian): The teams are happy and dare to argue, the leaders listen. You can see that the French are a thriving people who have real freedom of expression. In Italy, you are afraid of being fired if you disagree with the bosses, those who progress are those who have a lot of influence, the important thing is to keep your place. We Italians should really be inspired by them and make this freedom of expression our own.

As in the first series of interviews, I put this issue at the top of the foreign partners’ list of concerns because it conditions a large part of professional relations, first and foremost communication between people of different status. However, the intensity of the hierarchical distance remains an element of surprise for many foreigners who consider the French context to be synonymous with freedom.

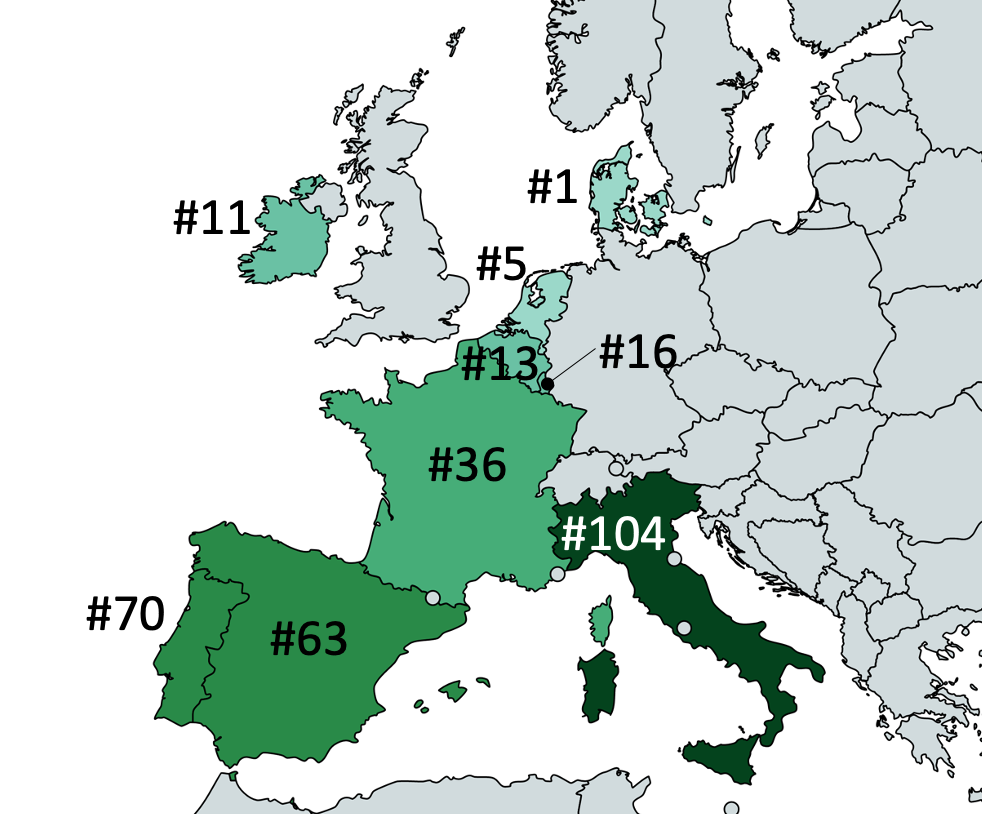

It should be noted, however, that everyone perceives the French context according to their professional habits in their country of origin. For example, the feedback from the Indian, who also had experience in the Netherlands, where people of different status are used to working with a high degree of egalitarianism, accentuates his perception of the hierarchical distance in France. The Italian, for her part, perceives the French context as much more open and free than in Italy, which is in line with the World Economic Forum’s 2018 ranking on the willingness to delegate authority at work: out of 140 countries, Italy ranks 104th, France 36th and the Netherlands 5th (source here, pdf).

I quickly made a map with the ranking of some European countries:

2. Feedback

Maryam (Moroccan): I find that the French don’t take the time to debrief. It’s not automatic. Most of the time it is more like a checklist. They don’t go into the details of what happened.

Klaus (German): In terms of feedback, I often had to ask the French, “So, how do you think it went? Are you happy with the result?” If something went wrong, unfortunately it was the same. I had the feeling that it had to come from outside, that it wasn’t really coming from them. With my French colleagues I rarely felt that they had to say “let’s talk about it”. It was more like “OK, the damage is done” or “it’s over” and nothing more.

Carla (Italian): I think there is little feedback. In my country it’s almost an obligation and I personally try to give negative as well as positive feedback. I have the impression that in France there is less of this culture, or they do it in a more limited way, in small teams among themselves.

Jakub (Polish): In France, I notice that it is less common to get constructive feedback about the situation that has occurred and recommendations for improvement. In Poland, when there is a problem, it is more common for me to get feedback on what needs to be improved in my communication, in my behavior, or on a technical level. In France, people will tell you that you did something wrong, but they won’t always tell you what you need to improve.

Paloma (Brazilian): If the French were an animal, they would be a duck, because they make a lot of noise and they have a difficult temperament! They grumble a lot, they criticize France, its internal politics, they grumble about everything and especially about their professional sphere. They will criticize human relations, working conditions, without ever questioning themselves or realizing how lucky they are to work with so many rights.

The ability to give constructive feedback remains a black mark on professional relations with the French and, one might add, among the French themselves. We certainly do not have a monopoly on it, but we can wonder about the Franco-French reasons for such difficulties in expressing, listening to and taking into account constructive feedback. We should certainly go back upstream to the educational system, which does not encourage a culture of constructive feedback, a positive relationship to error and failure, a less personal approach to knowledge and ignorance.

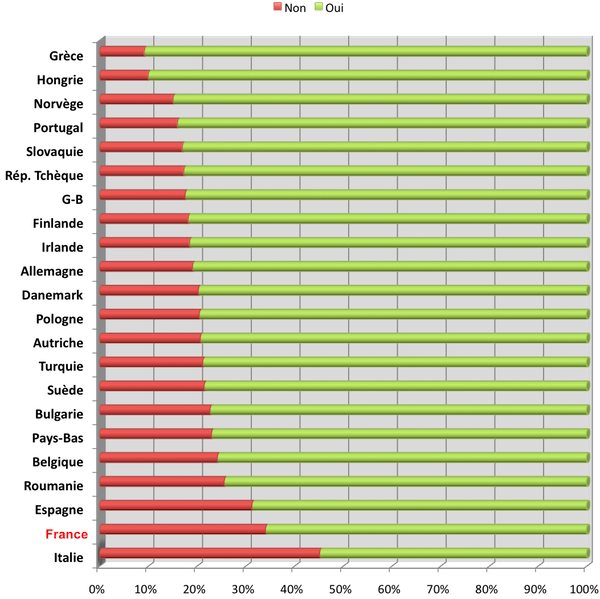

It is as if a large part of the construction of the personal identity of the French is primarily the result of a definitive mastery of knowledge and not of a lifelong learning process. In 2010, I published an article about 5 disturbing peculiarities of French management, where one could read about France’s very low ranking on the question: “In general, does your manager or supervisor give you feedback on your work? [Oui stands for yes].

3. Meetings

Klaus (German): The meetings were usually more like briefings, because it wasn’t really about listening to others; it was more like “I’m telling you news, and I’m not really interested in hearing anything back”. Decisions couldn’t be made in a meeting. They had to be made informally after the meeting. It was never clear how information was communicated. It wasn’t that transparent. The decision was never really related to the meeting that had taken place earlier on the issue.

Ahouéfa (Beninese): At first I was shocked by the number of meetings, but eventually I understood that it was also a way to meet, to talk to each other, and just to discuss. They are also very long because we are going to take the time, I would say lose the time, to get into the issues. There is this side where we will talk a lot first, explain again the context, the outlines, and all these are things that should be done before coming to the meeting.

Veera (Finnish): I have also worked on French projects as a collaborator. In terms of deadlines it was fine, but the meetings we had were too long. The French discuss a lot and in the end things are not decided. You have to have a lot of meetings to decide things. Those long meetings were not effective. It takes a long time to make a decision. In Finland we like short meetings (15 minutes) where we make decisions.

Julian (Canadian): We, in terms of communication, we get right to the point, we don’t waste time. For example, we don’t read a lot. So if you give me a report that’s a sheet of paper, you can be sure we’re not going to read the whole sheet. Even worse, if the report is on multiple sheets! In the two or three sheets, the Frenchman will want to define the purpose of the meeting, to explain the details of each other’s opinions. We just need the purpose of the meeting, the broad outlines. We like to keep it short, simple and to the point.

Assane (Senegalese): In a meeting, it is easy to go off the agenda. It all depends on the person leading the meeting. If he or she gets carried away or loses control, things can go in any direction. You need a bit of authority in meetings because everyone wants to defend their ideas and someone has to referee and say stop. For me, this is very characteristic of meetings with the French.

Shaun (British): If the Germans tend to make robust things that work well, the French tend to have a strong sense of aesthetics, of beauty. In meetings you have to be well dressed because dress is very important to the French. They have a strong taste for the visual aspect (aesthetics), whereas the English, if you work with him, if he knows that you will do your job well and that you will bring him money, he does not care about the rest.

Maryam (Moroccan): Another thing, I don’t know how to say it in one word: the French love meetings! It doesn’t matter the situation, the employer. Really, I don’t know why. I don’t know why they like to say things again.

Heather (American): Many people attend meetings without preparing for them, as mere spectators. That’s why so few people speak. The problem in France is that there is training on how to run a meeting, which is good, but the problem is this tendency to overcomplicate simple issues.

Assane (Senegalese): I have also often noticed that the participants do not prepare the meetings. Often they discover the topic in the room. Often, during the meeting, we collect information that should have been prepared beforehand. And finally, it is at the next meeting that the topic is actually discussed. So instead of having one meeting for one topic, we have two or three, because we take the time to explain and discuss the agenda again, when it should have been done before. A lot of times other people find out about it right away and since they don’t agree with it, we end up wasting time and having to reschedule a meeting to discuss it.

Liam (Canadian): You get a lot of pushback if you challenge their point of view without some diplomacy. When faced with a contradiction, the French prefer to find a solution immediately, even if it means prolonging the meeting, and they don’t like to lose face.

According to a 2018 IFOP survey of a sample of 1,001 people representative of the executive population (here, pdf), French managers spend more time in meetings than they do on vacation, 27 days a year. More seriously, 78% of French managers say that their opinions are rarely, if ever, taken into account by the company’s executives when important decisions are made.

4. Communication

Ahouéfa (Beninese): The very hierarchical aspect weighs on the way we communicate, on the top-down communication. The information goes through several filters before it reaches us, and this creates suspicion and sometimes we feel less concerned. Sometimes this has a negative impact on the overall involvement.

James (Canadian): Canadians are generally open to sharing information, to working together. I have found that some French people tend to keep information to themselves. Canadians are happy to be asked for information and are happy to share what they know when asked.

Veera (Finnish): With the small team I had, communication was very direct. We discussed, gave our opinions. But with the other experiences, the communication was very indirect, a very political language was used, especially by the top management.

Themba (South African living and working in Canada): The French ask a lot of questions during the meeting and sometimes they like to debate on certain issues. It is worth noting that there is a lot of non-verbal behavior that can clearly be interpreted in a positive or negative way. This behavior often leads to reactions that make me feel not included. I was aware of this feeling every time the French raised their eyebrows without saying anything.

Maryam (Moroccan): The French are direct. They don’t beat around the bush. They are talkative, most French people talk a lot. Sometimes they talk about everything and nothing and we get distracted.

Carlos (Colombian): Communication with the French was direct. They got right to the point. The French were very open in their exchanges. We found a synergy in the conversation very quickly.

Liam (Canadian): Are the French sufficiently receptive to third party suggestions to move a project forward? It depends on the person in front of us and the relationship we have with that person. In general, you have to prove beforehand that your opinion counts with a French person. The hardest thing is to take the plunge, to try it for the first time.

Aleksandra (Georgian): In France some things are slower than in Georgia. There is also a little more formality in the work: e-mails are a little more formalized, more structured. After every meeting, you have to write a summary or a report so that everything is clear. Writing, writing, writing! We need to write a lot more.

If we had to summarize the challenges that foreigners face when communicating with the French, we would say that they are confronted with a surprising culture of debate in a hierarchical context where form counts as much as content. For the French, this is not surprising: they are used to long discussions, to adapting their communication style according to the hierarchical position of their interlocutors, to choosing the right words and expressions, both oral and written, according to the situation, the person, the status, the level of knowledge.

For foreigners coming from more direct communication contexts, such as Canada or Finland, this is a major obstacle to cooperation. During intercultural training, I have to insist on the need to take into account the importance of politeness, which in France determines the form of the message, for example the more frequent use of the conditional when making a suggestion or asking for something.

5. Explaining, arguing, convincing

Michel (Lebanese): Immediately I noticed that there was a lot of talking, sometimes not for much. We have to listen to them and that was a surprise for me. When the Frenchman wants to achieve his goal, his objectives, he wants to impose himself. Of course, this is not a specific mentality of the French. It is rather when they are sure of themselves that they try to impose their line. In general, I appreciated that everyone was free to express their opinions and ideas. I even noticed the positive side of this freedom; the men in the field sometimes manage to change their boss’s mind. So it’s not a strictly vertical relationship.

Aleksandra (Georgian): In France, if a person says, “I don’t agree”, he will say I don’t know how many sentences after that. In Georgia we say yes or no, and sometimes it can be too brutal. But we don’t use as many sentences as in France to express ourselves. With the French, there is a lot of politics in everything. If you want to talk about something, you have to think about it who knows how many times!

Ahouéfa (Beninese): Globally, questioning the thesis of French colleagues, their point of view, can be complicated, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it, but when you do, you have to be prepared for a potential conflict, I would say a strong opposition. In fact, generally people have a pretty precise and clear opinion on things and you come with the aim of telling them they’re wrong and immediately you have to justify yourself, it’s not just, oh yes, you’re right, it’s also going to be: why are you saying that? What are you basing it on? I think there’s a lot of ego involved, and not just the intellectual aspect. Anyway, I’ve noticed that with the French you have to be prepared for long discussions if you want your word to count.

Julian (Canadian): The French beat around the bush when there is something to explain. I get the impression that they don’t get to the point. And that bothers us on the American side. We are not there to listen to rhetoric, we are there to know exactly what happened in order to draw conclusions. For example, if we ask the French what color a boat is, they will first explain the origin of the boat, the context, before finally saying that the boat is blue. But we would say directly that the boat is blue.

Carla (Italian): I have noticed the ease with which the French take up the topics and their pedagogy. Their reasoning is detailed but clear. They go from the global to the detailed and adapt to the level of the interlocutor. For example, with me they stayed at a macro and strategic level, but with the engineers in my team they went into much more technical detail.

Moussa (Cameroon): The French are very pedagogical, they like to feel that they are being gradually led towards something, but in a clear way. In writing, there are French people who like the text, they like to see that there are well-constructed turns of phrase, with a sustained vocabulary and all the rules of politeness that go well.

Greg (British): The Englishman thinks the Frenchman is a good talker. But he talks a lot and doesn’t get to the point. He goes from left to right in a meeting, leading you in before closing. In fact, he is good at demonstrating, he takes his time to do a lot of demonstrations, which is not perceived well by the Englishman because he has the impression that he does not get straight to the point.

Lucas (Belgian): They need time to think before they make a decision. They need to develop their thinking before they act. They need to think, they need information, so they need time. It is important to talk to them to know their priorities. If they need time and delay, it is not a problem because they are transparent and flexible.

James (Canadian): During a meeting, some French people will say “that’s not the way to do it” if they have a different opinion or they don’t agree with you or what you’re saying. They say it immediately and you can see it in their face. In Canada, it’s frowned upon to tell someone curtly that you disagree with them. We avoid attacking the other person directly. Everyone has a point of view, and all points of view are equal. After that, of course, we find a consensus.

Assane (Senegalese): The discussions are very often lively, there are debates of ideas. The ideas that come up are very well argued, whether for or against. I also noticed that when you get into a debate, they are very defensive. I have an anecdote here: when I arrived at a client’s site to develop a small application for a project, I went through the code and made suggestions to the developer on how to code. I suggested to him to do it differently, I tried to convince him, to explain him by A + B, but it had no effect. And most importantly, the discussion went in all directions. So I left him alone and continued in my own way. Some time later, he came back to me and said that he had looked at my code and found that the best way to proceed was mine. In the end, he made it his own. I concluded that there was probably a lack of humility and a complex problem.

French-style communication cannot be understood without our culture of debate. And this culture of debate is one of the consequences of our style of argumentation. This includes the dialectic of thesis and antithesis that the French learn in high school philosophy class, in other words, contradiction. We like to pit our brains against each other, taking different points of view, sometimes even playing devil’s advocate, i.e., presenting a point of view that is not our own, with the sole aim of arriving at a realistic or innovative position.

The French then tend to unfold their written or spoken discourse in funnel mode: starting from the global to the detailed. And they think that this process is universal. Wrong! It can be perceived as a waste of time, aggressive, or arrogant, by foreigners who are uncomfortable with the idea of debating and destabilized by ideas that certainly come up, but which are sometimes not planned in the meeting agenda. On the other hand, the French can take the time to explain their ideas clearly and pedagogically and, whatever the culture of their interlocutors, speak as equals, from reason to reason, from intelligence to intelligence.

6. Work/life balance

Klaus (German): In general, the French I’ve met have a bit of a “I love my vacation” culture. They go away and become unavailable. There has to be a really high work priority for their vacation plans to be canceled. That’s what I’ve noticed. It’s more of a lesson to be learned. They have this attitude of, “My time off is my time off, I insist on it, and I get a lunch break, so I’m going to take my lunch break. Work can be done, but it has to be organized differently. And that’s something that can be inspiring and frustrating at the same time if you’re not in the same boat.

Themba (South African, lives and works in Canada): I found it inconceivable that the French are so strict about their lunch breaks. They all take breaks and stick to them, as if missing them would be frowned upon or a problem. In North America, the notion of “time is money” means that every minute counts to make an extra dollar, but the French can politely tell the customer, “It’s my lunch break,” and the customer has to come back after. But I learned and quickly understood that the French are very sociable and like to take their break at the right time to catch up with their colleagues who are sometimes waiting for them. In Canada, you can leave work early (4:00 to 5:00 pm) if you didn’t manage to take your lunch break.

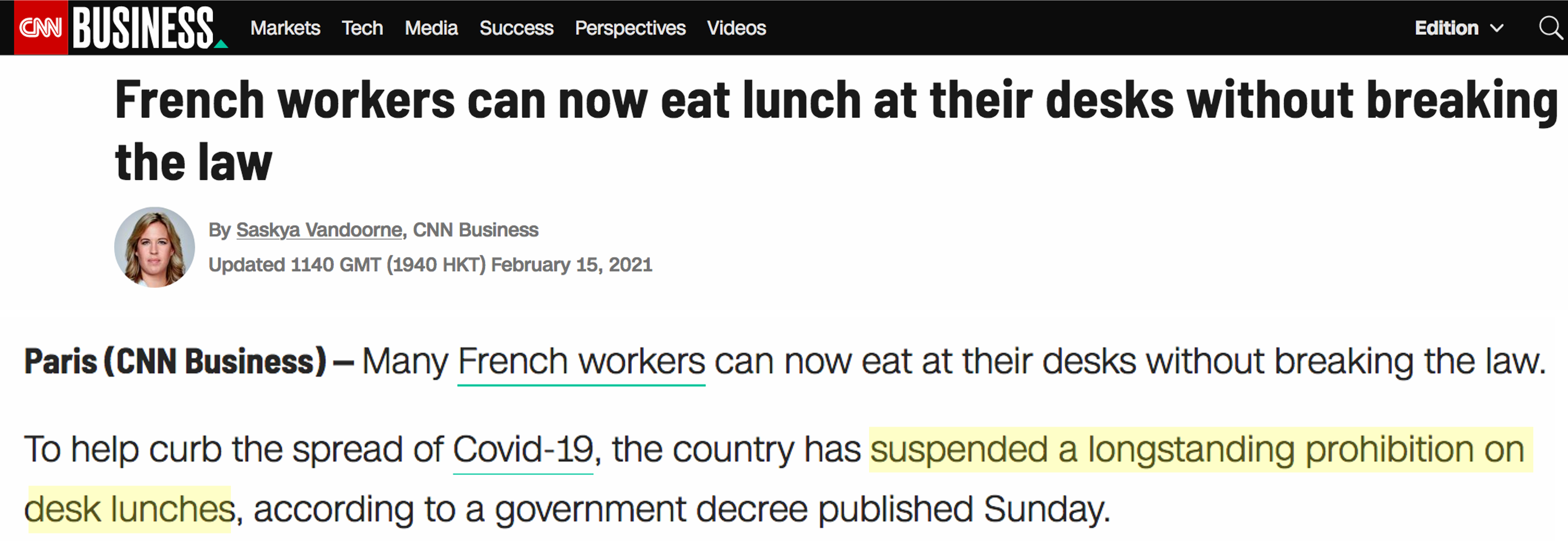

Jakub (Polish): What I like in general is that in France, especially the older generation or people with a little more experience, their personal life is more important than work. Of course, work is important, but their private life, their private business, their vacations and their breaks are very valuable. When people go on vacation, they don’t think about work, they completely disconnect, they enjoy it. And when they’re with their family, they’re with their family, they’re not at work. And I really like that. I really liked that model, which in a way also translates into the fact that the lunch break in France is quite long.

Maryam (Moroccan): I also find that in France, in terms of education and extracurricular activities, they all have things to do on a daily basis in parallel with work. They have a real life. The French give time to everything. That’s what I’m learning from the French: to do something other than work.

Aleksandra (Georgian): In Georgia, the balance between work and private life is not respected at all. It’s like you get an e-mail, a message, even on the weekend. If it’s urgent, you answer it. And you get a phone call, especially if you work with foreigners, you’re always available. And especially if you are in business. If you’re in business, you send e-mails even at 11 o’clock at night or even later at night. And that’s almost normal. You can be on vacation and you get emails, you respond immediately, even if you are on vacation. And your boss, he thinks it’s normal too, and everybody else thinks it’s normal.

Moussa (Cameroonian): The Frenchman is not available after work, as soon as he turns off his PC, his work is done. If you call him once, he will complain. If he is still working on the subject you are asking him about, he will certainly point out that he has already done so with several people or on several occasions.

Carlos (Colombian): The French manage the balance between social and professional life better because they are more organized and aware of how many hours they have to work and how much time they have off. This affects daily life. I have learned this from experience. In Colombia, the lack of discipline and organization leads to a constant overflow of time; work life encroaches on personal life.

Ahouéfa (Beninese): The importance of holidays and vacations, breaks and lunch, these are really precious things for the French. They give their best when they are at work, and they give their best when they are on vacation!

First, foreigners are often annoyed by the ritual of lunch breaks or vacation absences, which force them to follow the rhythm of the French, who show little or no flexibility in these matters. Second, the French ability to “cut back” and “disconnect” is admired and even envied.

7. Interpersonal relationships

Maryam (Moroccan): I find that here in France there is much more organization compared to Morocco. There is no one who interferes in the work of others. There is also no judgment. Even if there is a conflict at work, it does not affect the personal relationship. Unlike in Morocco, where it becomes personal. In France, I have always been able to express my opinion openly.

Elena (Romanian): What I like is this politeness that the French have all the time, but it comes from their education, from their way of life, I guess. You have to be polite all the time, even when you have a drink. I like that politeness that I felt in the native French. I have learned to keep a polite distance in all circumstances because it is better that way.

Veera (Finnish): You have to be polite, don’t ask for too much, let it go. You can make an enemy on the first day if you show that you are his or her equal, because he or she thinks he or she is superior. It is important to watch who is who, because you can easily make enemies and they make your professional life difficult.

Aleksandra (Georgian): At work, what surprised me, there is something, how to say, an important point about the salary for example. In Georgia, almost everyone knows the salaries of others. It’s a very open topic. I get so much, the other guy gets so much, and bonuses… It can be part of a conversation over coffee. It’s not a secret. But in France, I think it’s more of a taboo subject. Because you never ask your colleague how much he gets, how much bonus he got. In Georgia, on the contrary, we show them. It’s good to show it, there are no constraints to show income, salaries or to buy nice cars or houses.

Julian (Canadian): The French don’t reveal themselves right away, they hide things at first. After a while you’ll understand exactly what he wants. If he needs something, he won’t tell you right away, he’ll beat around the bush.

Elena (Romanian): Romanians, when we see each other, we ask, “What town are you from? Where did you go to school? How are your parents?” With the French, these questions come later, when they see that they can trust us, that we belong to the circle of accepted people. Then there is a warm, comfortable closeness. I like that at some point, when they know that the cooperation will be long, they show their curiosity about traditions, places to visit. When a Frenchman comes to Romania for three days, we talk about work all day, at lunchtime or in the evening. But they start asking: “What can we visit here? What historical remains do you have? What museums can we visit? What are your traditions?” They could remain neutral, indifferent, but they don’t, and I like that.

According to the writer Jean Cocteau, the French are bad-tempered Italians. Wouldn’t they rather be friendly Germans? Or simply French? In other words, people who are very task-oriented and at the same time very much in need of strong interpersonal bonds, provided they are built very gradually.

So what comes first? The task or the interpersonal connection? Both! So at the same time? Yes… but… as disturbing as the chicken-and-egg problem is, it is also a positive surprise for strangers who, after an initial period of polite distance, discover the strength of interpersonal bonds. Unfortunately, this was not the case for the actress Natalie Portman, who did not know how to adapt to the French context during her expatriation in France:

8. Barriers, challenges and glass ceilings

Liam (Canadian): France has a selective, social class culture, consideration is generally given to a colleague who has experience in large groups or who has graduated from prestigious schools; professional experience, expertise are not considered at their fair value.

Heather (American): In France, if you want to change your career path or your job, you’re often told that you need to get training because you don’t know anything about it. So, yes, training on more technical subjects can be useful and relevant, but the idea of using an opportunity to make people evolve, to make them pivot in their career, is very complicated. You could compare it to the glue effect: your job or department sticks to you so much that you can’t imagine being anywhere else. You don’t want to admit that there is a connection, even though there often is. The fear of failing to transfer skills outweighs the opportunity to grow and potentially add value to another department. The risk of lack of competence is always cited. On-the-job training and experience are not taken into account.

Maryam (Moroccan): In Morocco, there have never been more men than women in the sector where I work, which is more technical (automotive sector). And women are much more numerous than men in the market, we dominate, so there is no difference. The salaries are the same and you have to negotiate whether you are a man or a woman. On the other hand, in France, I know that there is a difference in salary. If you are a woman, the salary range is not the same. When I was looking for a job, the French human resources department clearly told me that the range I asked for was more for men. Apart from the salary, there is also a difference in terms of the behavior and the mission that women are offered. For example, during an interview, the recruiter clearly told me: I’m going to give you a less difficult assignment because you’re a woman.

James (Canadian): The French can use their diploma. It’s true that degrees count, but here in Canada it’s not something to brag about. What counts here is what you can do and showing that you know your job well. Showing off your diplomas is interpreted here as pride, as a desire to put others down.

Elena (Romanian): The French think that if the information comes from France, it is more important than if the same information comes from Romania, even if in the end it is the same information.

Assane (Senegalese): When you first arrive, they look at you a little suspiciously, they try to put you in a situation. To be respected, you have to prove yourself and earn your place at all levels. When I arrived, they gave me complex things, they left me on my own without much help. When I delivered, it was shown to the management, and when I was given new tasks, the project manager said in front of everyone that I could be trusted and that the work would be done well and quickly. That’s how I understood that it was a test of my skills. As a non-French member of the team, I felt that I had to work harder, that I had to prove myself twice in order to win, which I had already felt when I was hired.

Greg (British): I don’t like the fact that they complain all the time. The Frenchman wouldn’t just say something was good. He would say, “It was good, but did you see that little thing? He always expresses himself with reservations or it’s always with negative remarks. The Englishman is the opposite: even if there are negative aspects, he will tell you that it was good. In fact, if he sees that it might hurt, he will drop it.

Liberty, equality, fraternity? When the beautiful French motto meets reality, it loses some of its luster. Every cultural context has its strengths and weaknesses in this matter. Again, some will be found more often in France than elsewhere, and for reasons specific to the French social and historical background.

There is an image that I’ve kept since I saw it in 2014 (I can’t find the source, sorry for the copyright, but I’ll include it if it’s pointed out to me) that sums up a multitude of specifically French issues. It is an exchange (staged for communication purposes) between President Hollande and his Prime Minister, Manuel Valls. One can see in it a desire for closeness and equality between the two men, sitting around a very modest table, but in a prestigious setting. Can humility be achieved in a palace that materializes hierarchical distance? And is the display of humility a proof of humility? Here is a knot of contradictions that can also be found in companies.

Quelques suggestions de lecture:

- Working with the French: Indians share their experiences

- Working with the French: 17 foreigners from 12 countries share their experiences

- Cross-cultural Turbulence at Air France-KLM: employees share their experiences

- The surprise effect, or the enemy of cross-cultural communication

- Intercultural meetings: 10 good practices to reduce misunderstandings

- Working with the French – feedback from the field

Derniers commentaires