English version of Les systèmes éducatifs, clés essentielles de compréhension des différences culturelles

8 stories of small annoyances and big misunderstandings

Invited by Chinese authorities for possible partnerships, directors of French “grandes écoles” [elites schools] traveled to China and began the meeting with long and boring speeches outlining the philosophical principles of French-style education, while their interlocutors expected to exchange directly on the proposed courses of study and potential opportunities for their students, rather than listen to the long genealogy of the “honest man” from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment.

Within a French-Belgian energy group, the Brussels-based team was surprised to see a document it had sent to the Paris offices being returned to it with red corrections to the few French Belgian expressions it contained. In the e-mail, the sender made a point of specifying: “We are sending you back your corrected document in French.”

In a French-German company, meetings between French and German colleagues are regular, and very regularly they give rise to mutual annoyances: the French go from the general to the individual, while the Germans go from the individual to the general. The former seem vague and unreliable to the latter; the latter seem to lack seriousness in the eyes of the former.

In a French-German company, meetings between French and German colleagues are regular, and very regularly they give rise to mutual annoyances: the French go from the general to the individual, while the Germans go from the individual to the general. The former seem vague and unreliable to the latter; the latter seem to lack seriousness in the eyes of the former.

In Nigeria, the French HR Director of a major energy group gives a speech to motivate employees who have been promoted to the rank of manager. He asks them what is most important for a manager: to be or to do? And he begins to argue at length that “the debate has never been settled between René Descartes’ focus on justification by action and Socrates’ injunction that there can be no action without being.”

French instructors in charge of training young Chinese to become airline pilots appreciate their ability to memorize and transcribe the information in the manuals very accurately. But they don’t understand why they find it extremely difficult to vary this same information according to circumstances and unforeseen events in flight situations.

Invited by its American partner to present its approach of innovation, a French team could formulate a theoretical definition of innovation after many meetings and intense discussions. But, having become aware of its overly conceptual approach, it revised its mind and ended up proposing three stories of innovation, one dating back ten years, one dating back five years, and the last one very recent, in order to explain the evolution of its approach to innovation. This “storytelling” approach, unprecedented on his part, was met with strong reticence from some team members who found this way of doing things lacking in seriousness and intelellectually not satisfying.

The HR department of a British company with employees coming from many different countries was surprised: why is it that, following a training course or a conference, French employees are most of the time the only ones not to give the most positive appreciation?

An Air France employee commented: “I see a big difference between Air France and KLM in terms of the speed with which ideas are spread, whereas at Air France, you first think deeply, take a step backwards, do studies, etc.”. One of his Dutch colleagues explains that “facts, facts, open debate and a voluntary attitude would help us enormously” and would like the French to “make it possible to discuss things as they really are. “(see on this website: Turbulences interculturelles chez Air France-KLM: employees testify).

Back to basics: education

I have chosen these eight stories from the vast database of cross-cultural anecdotes collected over nearly twelve years for three main reasons:

- First, they are recurrent and testify to a certain French specificity, at least trends that are more frequently found coming from the French rather than, for example, from the Americans or the Japanese.

- Secondly, they teach us as much about the French as they do about their foreign partners: we are there in the mirror effect of intercultural relationships. Thus, the meeting between French and Germans informs us about both of them in terms of their way of arguing and convincing, just as the astonishment of the British at the lack of positive assessments also indicates a tendency on their part to make more positive assessments.

- Finally, we are confronted here with cultural differences regarding the conceptual approach, the deductive or inductive process, the learning style, the place of argumentative debate, the value of philosophical reasoning, the time for reflection in relation to the time for action, the tendency to correct abruptly or the difficulty in sharing positive feedback: these are all particularities on which many foreigners question us during training courses.

To understand is not only to describe effects but also and above all to explain by causes. This is one of the major challenges of intercultural training, with the ability to identify and adjust certain practices for better mutual understanding and more effective cooperation.

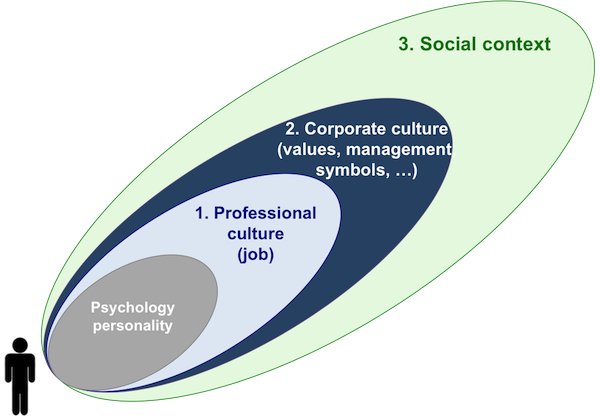

So, where do the particularities indicated above come from? Are they due to the personalities of the protagonists, or are they due to differences linked to professional cultures, corporate cultures or even so-called national cultures (for my part, I prefer to speak of the influence of the “social context” to avoid reducing cultural complexity to the “national” level alone)?

Most of the time, we are dealing with a complex cocktail of these explanatory dimensions among which, instead of isolating a single one as an explanatory element, we try to determine which is the most important center of gravity in this or that experience feedback. In terms of the social context, it is a factor that is often overlooked or too quickly mentioned, even though it has strongly contributed to shaping and forming every individual from early childhood to adulthood: the education system.

The faces of foreigners to whom I detail some of the peculiarities of our educational system suddenly light up (oh, the famous “dissertation”!… oh, the philosophy course!… and the formal lectures!…) and they understand better, for example, why 57% of French employees follow their manager’s instructions only if their reason is convinced, compared to 21% of Danish employees (see on this website Working with the French, feedback from the field).

So let’s go back to the source and look at children’s drawings, for example. In a fascinating article entitled “Draw me a man”, Universaux et variantes culturelles (pdf), pychologist René Baldy shows the drawings of two ten-year-old girls, a Swedish girl (drawing on the left) and a Tanzanian girl (drawing on the right), who were asked to draw their classroom:

The little Swedish girl draws herself in the center of the class and her teacher is very close to her, reaching out to her, in an attitude where we can read the intention to put herself at her service, to work for her: it is the pupil who is at the heart of the pedagogical relationship. It is the opposite with the little Tanzanian girl relegated to the back of the classroom, tiny compared to the distant and gigantic teacher.

Here we meet educational systems based on extremely different values that largely shape individuals’ relationship to authority, communication style, public attitudes or self-perception. In the long run, it is not surprising that the adults who have come out of these systems find themselves in very different managerial relationships, with for some the obvious need to put themselves at the service of their collaborators when they are managers, and for others the need to put themselves at the service of their manager when they are subordinates.

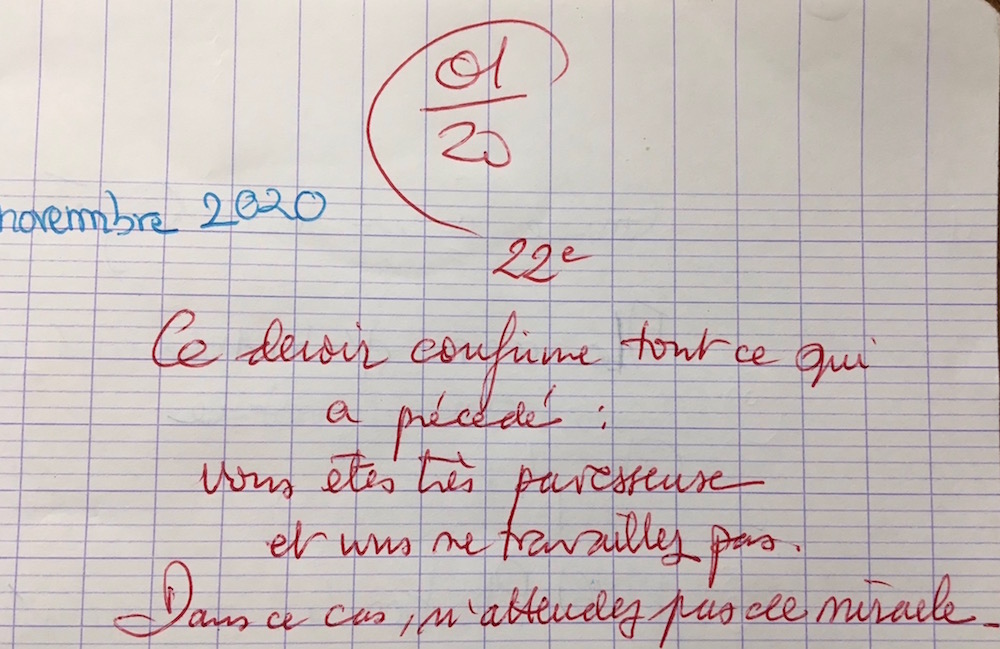

Regarding the French tendency to abruptly “correct” foreign partners, I let you appreciate what the mother of an 11-year-old student tweeted just two days ago (I won’t show the full tweet with the name as this person subsequently deleted her message):

[translation: This homework confirms everything that came before: you are very lazy and you don’t work. In this case, don’t expect a miracle.]

A quick journey round the world of education systems

I always encourage partners from different countries to exchange as much as possible about their respective education systems. Similarly, when I have students of different nationalities, I have them work on their education systems, from primary to higher education, to identify with them significant keys to explain certain professional issues.

For a number of years, I have been collecting testimonials and articles on the subject. I am going to share here a few excerpts which concern both early childhood and higher education and which are not intended to analyze in detail the education systems in question but which have the value of testimonials that also shed light on cross-cultural issues, particularly with the French, with regard to relationships, reasoning styles, preparation for meetings, communication styles, the practice of feedback, the relationship with hierarchy, teamwork, etc.

United States – Sharing, trust and empowerment

United States – Sharing, trust and empowerment

- Trainee Teachers from the Montpellier Academy in immersion in New York schools (source):

Instead of reading the same book, the students choose one from the classroom library and read it independently, with the teacher having to ensure that the book is at the student’s level. Then the children share what they have learned in working groups of usually five children. They develop their speech and are strongly encouraged to communicate with the other children. This method has caught the attention of the trainee teachers since it is repeated until the end of elementary school, whereas in France the pupils sit in line in front of the teacher from elementary class.

As the teachers, principals and trainee teachers themselves say: “the teacher is a guide who accompanies the children towards the right decision”. The American teacher does not give the lesson as a French teacher would, he gives the instructions and then lets the children learn alone. And when they make a mistake, he does not correct them but helps them find the right answer on their own. The philosophy practiced here aims to give the child confidence, motivating his efforts to learn more.

- Excerpt from the article Jeunes: le pessimisme des Français contre l’enthousiasme des Américains (source):

Young Americans are encouraged early on to take on responsibilities and take an active role in the community: high school magazines, public speaking, fundraising for extracurricular projects, volunteering, odd jobs, personal discussions with teachers, etc. The effect of these initiatives is to reduce the hierarchical distance between young people and adults, as well as to foster the feeling that it is possible to have a concrete impact on things.

Quebec – Home or open-book exams, courses prepared in advance

Quebec – Home or open-book exams, courses prepared in advance

- Lisa Inganni, eight months on exchange at the University of Montreal in her final year of law school (source):

The exams are completely different, and often in the form of “take-home” exams to be done at home. They were either course questions or research assignments, which we were often free to choose the subject, and which required a lot of work time and a very precise layout: a guide indicated how to present the references and the bibliography. I really liked these homework assignments, which required a great deal of rigor, while at the same time allowing us to use all the resources we might need.

There are also table-top exams, but they are very often open-book exams, with the course, the reference book, and other documents made available by the professor for the exam, who will sometimes give more thought to them.

- Testimony of one of my students from the SDAI master’s program at the Ecole Centrale, collected in 2014:

Students must prepare the course in advance from documents given by the teacher. And they receive always positive comments on their work or when they speak.

The Netherlands – A resolutely pragmatic approach

The Netherlands – A resolutely pragmatic approach

- Caroline Rey, trainee of the second degree in Modern Letters at the Hogeschool Rotterdam (source):

The educational priorities of the Netherlands are the development of skills and know-how rather than the acquisition of encyclopedic or even critical knowledge. …] Dutch liberalism is based on a tacit contract of obedience to established norms. Far fewer rules, but well-accepted rules. Transgression is never a positive value, progression is. The student is autonomous, individualized education. The child, in fact, is the own master of his learning. He knows, in advance, the program of the term and can thus go at his own pace and advance in the subjects where he succeeds best. A student’s progress in a subject should not depend on the progress of the class group.

In the college in The Hague we visited, the teacher had recreated a real small French village with its restaurant, café, mini-market, youth cultural centre, police station, train station and tourist office. I was personally assigned to the restaurant “Les trois brasseurs” where I served as a waitress. The students had to be able to ask for a table, order their meal and ask for details about the dishes on offer, congratulate the chef or on the contrary tell him that his entrecote was not cooked, and finally ask for the bill after politely refusing the coffee offered by the house.

- Testimony of Vincent Merk, teacher at Eindhoven University of Technology and living in the Netherlands for almost 40 years:

In the Netherlands, the famous consensus is learned from a very early age in primary school where on Monday mornings the pupils sit in a circle and tell about their weekend activities and everyone listens and waits their turn to speak. The circle is also very important, as it can be found at social or family events such as birthday parties, etc.

Germany – Personal development and specialization

Germany – Personal development and specialization

- Excerpt from L’école en Allemagne (source):

Germans prefer an education that fosters individual development: the “Bildung” (a reference to the German tradition of self-cultivation) is the basis of their educational system. According to them, the child must grow and develop his personality, individuality and his own talents. In the classroom, this means a lot of discussion and small group work to encourage children to talk, debate, be critical and listen to others.

Unlike in France where the aim of the school is primarily to transmit knowledge, the aim of the German school is to produce children who are well-balanced and capable of living in a community.

- Testimonials of French people who have participated in International Exchange Programs (source):

Classes [at the high school] take place from Monday to Friday (very rarely on Saturdays). They last 45 minutes. They start between 7:30 and 8:00 depending on the ‘Länder’ and finish between 13:00 and 13:30 or between 15:00 and 15:30 (depending on the day and the subjects chosen). There are never more than two afternoons of classes in a week. The rest of the day is mainly devoted to sports, parallel activities (club, art…), discussions, work at home.

The atmosphere in class is much better [than in France] – it discusses, it debates, the teacher’s voice is not the only one to be heard – unlike in France, the teacher in Germany is neither the king nor the emperor.

The surveys highlight the importance of musical practice (individual lessons, orchestra, chamber orchestra). The practice of sports is relatively important (between 2 and 4 hours) and above all more specialized than in France, since a student chooses a sport for the whole year (basketball, soccer, judo, karate, volleyball, badminton, dance, canoeing), and that he is becoming more refined in this area.

Italy – Oral skills and negotiated assessment

Italy – Oral skills and negotiated assessment

- Extract from the symposium proceedings The challenges of intercultural communication: linguistic competence, pragmatic competence, cultural values, MSH, 2007:

The experimental approach with problems and hypotheses is reserved for scientific discourse and is not really used in secondary education. Hence a certain drift if we put Italians in the position of discussing “anything”, whereas the school culture has accustomed them to expose knowledge according to an internal structuring of the particular subject.

There are also strong differences in the culture of evaluation. For example, at the “baccalauréat” level [O’Level], the college jury is essentially made up of internal professors. The oral exam is interdisciplinary, based on a prepared thematic dissertation followed by questions of precision on certain points of the discipline. The oral exam is also an opportunity to discuss and correct the written exams.

At the university, the exam is essentially oral, hence the oral communicative competence of young Italians. The evaluation is immediate, the grade negotiated and explained. Failure is not penalizing, there is a script to get out of the exam situation. There is no evaluation below the threshold of acceptability. Therefore, attention is paid to the maintenance of the candidate’s face.

Spain – A more empirical approach to mathematics

Spain – A more empirical approach to mathematics

- Comment from Sylvain, reader of my article Les Français et le démon de la théorie: 3 anecdotes (source):

I have been able to notice and experience the differences in the way of approaching mathematics in France on the one hand, and in Barcelona (or even the rest of the world) on the other.

I was already aware of this since the many international students in my school are very disgusted by the way of approaching mathematics in France. Indeed, in my school, the emphasis is put on definitions, demonstrations, then on rather abstract problems… and finally everything is oversimplified in tutorials to the point where the course and the tutorial classes have nothing to do with each other anymore.

Result: by caricaturing, you don’t understand anything in class (despite a considerable amount of knowledge acquired in prep school) and the tutorials are useless. In Barcelona, on the other hand, the emphasis is on examples and calculation exercises. The theoretical aspect will perhaps be addressed, but more quickly and also more easily because they are induced with examples. I also didn’t have any tutorial classes, which allowed me to work in the library, alone or in a group.

I would also like to point out that giving priority to theory also has a practical side! During my semester in Barcelona, I had a project in algorithmic. So it was quite formal and conceptual. It consisted in creating a program to optimize the storage of packages in trucks.

The project starts with a part of analysis and modeling of the problem to arrive at the algorithm that arranges correctly. All that’s left to do is to implement it and that’s it. For a French colleague and me: no problem. My colleague even managed to model and implement it in one afternoon.

The case of a Catalan guy comes back to me very clearly, because I was trying to help and guide him to find a good solution on his own. He was trying to find a mathematical expression of the algorithm (far from being trivial) in an empirical way! He imagined a solution and then tested it: it didn’t work. Then he would change a sign or whatever and start again! I can assure you that I finally spent more time helping my colleagues than doing this project.

Denmark – Course preparation and group work

Denmark – Course preparation and group work

- Paul Vignes, 20 years old, marketing student in Aarhus (source):

No more long days 8:00-18:00, no more monstrous amounts of work to prepare for the next day. Here, the only “homework” required is to come prepared in class, i.e. to have read the chapters that will be covered in the course the next day. I also have fewer exams but more group projects, because teamwork in Denmark is privileged and very much appreciated in companies.

Russia – Distance, respect for hierarchy and group spirit

Russia – Distance, respect for hierarchy and group spirit

- A head of a hotel school, testimony collected on this blog (source):

Here, the teacher is “God”, and the students silently wait to receive his word, unless “God” asks them by name and awaits an answer. It follows, in addition to this inability to spontaneously speak, a real distance and apprehension towards the hierarchy.

At school in Russia, one brings flowers on September 1st to one’s teacher, who is in most cases a woman. For New Year’s Day, a gift is given to her. The system establishes a teacher/pupil relationship that is at the same time distant, maternal and very hierarchical. For fear of being looked down upon, students will very rarely take individual initiative, and they will prefer to conform to the norm, even if it means not fully exploiting their potential.

Group work as such is quite rare in Russian schools or universities, but it can take place informally because students know each other by heart. Unless a student moves or repeats a grade, he or she will normally be with the same group of children at school for 11 years. The same goes for students, who are part of a “cohort” of 100 students and even a subgroup of about 30-35 people who have the same options.

- Feedback given by Jérôme Dumetz, teacher and consultant:

During the trainings I deliver, I have already experienced proof of the evaluation gaps between Russians and French. On a scale of 0 to 10, if the training is good, we end up with 10’s on the Russian side, and 7-8’s on the French side. The reason seems to be related to the grading system at school.

In Russia, we rate from 5 to 1: 5 means perfect, 4 means good but with some small mistakes, 3 is fair, and 2 is a failure (shame). 1 is never given. In France, 10 is the average (out of 20), but it’s not bad! With a 12/20 you have your head high, while a 14 or 16/20 is really class (well, in my time). With 20/20, it’s very rare, you have to have done as well as the teacher. Hence the disparate evaluations in spite of a similar feeling.

In Russia, exams are often oral and without marks, just a pass/fail appreciation. I must admit that after more than 15 years of teaching in many countries, I find it rather good (the grading system, not the oral one. I remain attached to an “egalitarian” exam, therefore written). But the most interesting thing about the Russian system is that even if everyone eventually gets a “pass”, the teacher can be quite demanding with a good student and rather flexible with a less good one.

Japan – Conformism, hierarchy and collective, importance of literary training

Japan – Conformism, hierarchy and collective, importance of literary training

In the school system of modern Japan, whether before or after the neoliberal reform, the art of arguing, argumentative skills, have no place in the curriculum. Japanese people who reason in everyday life are then despised, or even ignored. France, on the other hand, is the country of “dissertation” (long written school paper), which pushes this skill to the maximum at school.

It is always the company that dictates its law to the educational system. The goal of the educational system is always to train good employees, very honest, honest and competent. The school only provides a basis that will then be completed by the company according to its needs. Passing the competition and entering a prestigious university will define the social level of Japanese people. Meritocratic hierarchy at the end of the studies allows a social structuring of which the company will only be the continuity. One of the consequences of the lifelong employment system is that companies are not interested in a student’s specialization, which must above all be motivated, flexible and adaptable. The company will make him/her evolve according to his/her needs. All that is learned for the competitions is useless in the company. Young Japanese therefore feel they have sacrificed their adolescence in favor of excessive and unprofitable learning.

Those who succeed are recognized because they have passed their exams. Thus, when exchanging business cards, the name of the school or university is given to establish the hierarchy between individuals.

- A Japanese girl in high school in France (source):

I was very surprised that in France the teachers arrive at the school right on time to do their lessons and leave as soon as they finish. This is inconceivable in Japan. In our country, the teachers arrive around 7:30 in the morning. In the evening, they stay after classes, prepare files, the next day’s classes, and work together.

Contrary to France, the literary branch is the most sought-after, and also the most widespread, because it offers more opportunities. Only those who choose a purely scientific career (math teachers, biologists, doctors, etc.) opt for the “Scientific” branch. In Japan, jobs in the social, political and legal fields, as well as in business and commerce, are accessible primarily to those with a purely literary background.

Every day from 3:00 to 3:30 p.m. we clean the house. And not only our classroom. We are divided into three groups: the first group cleans the classroom, the second group cleans the toilets, the third group cleans the teachers’ room, and we turn every day!

Singapore – Priority to the concrete

Singapore – Priority to the concrete

- Excerpt from the article Comment les Asiatiques survolent les classements mondiaux (source):

The Singapore method emphasizes problem solving and systematizes a three-step pedagogy: students manipulate objects, then represent the problems with drawings before translating them into mathematical concepts.

“In Singapore, a teacher is not legally allowed to teach mathematics without a concrete object: if he gives his students an exercise that includes balloons, he brings balloons,” insists Mark Hartley, the principal of Barnes School, another London institution ranked in the top 5 of the best British elementary school, according to the newspaper “The Telegraph”.

* * *

Do you have other testimonials and experiences about foreign education systems? Feel free to share your comments below!

Quelques suggestions de lecture:

- Working with the French – feedback from the field

- The French and the demon of theory: 3 stories

- Working with the French: 17 foreigners from 12 countries share their experiences

- The absurd complex of the French towards the doctorate

- Meetings and the Decision-Making Process in Japan: An Interview with Dr. Sagi

- Cross-cultural Turbulence at Air France-KLM: employees share their experiences

Comme vous, je m’intéresse au système éducatif des personnes que je conseilles ou que je forme. Il y a néanmoins de plus en plus de personnes qui ont un profil culturel mixte: par exemple les familles d’expatriés dont les enfants fréquentent soit des écoles internationales soit des écoles locales. Dans de tels cas les enfants peuvent avoir des habitudes sociales très différentes d’autres enfants de la même nationalité mais scolarisés au pays. De la même manière, des enfants expatriés d’une même nationalité mais scolarisés dans des IB schools ou dans des écoles typiquement anglaises (A level) peuvent avoire des conditionnement culturels différents. Avoir ces données permet d’anticiper et de vérifier les possibles écarts avec les classifications à la Hoftsede. D’après mon expérience, ce qui importe c’est d’avoir les détails du lieu où les enfants sont scolarisés pendant les 10 premières années de leur vie.