As part of a MaCYB (Management de la Cybersécurité et Gouvernance des Systèmes d’Information) executive MBA course at the École de Guerre Économique [School of Economic Warfare], where I teach intercultural risk management, I asked teams of students to work on real cases of intercultural business situations, which they had to collect and analyze.

The cases are fascinating because of the diversity of situations presented and the students’ commitment to an unusual exercise. I would like to offer you a brief glimpse into their work with the transcript of an interview conducted by a team that chose to focus on the misadventures of a French woman in Japan.

Grégoire Aubin, Vignon Gnahoui, and Badaoui Salah interviewed Dr Sagi Srilalitha Girija Kumari, who shed interesting light on meetings and decision-making processes in Japan. Dr Sagi is Associate Professor & Chairperson Executive Education & MDPs, Department of International Business, GITAM School of Business, GITAM Deemed to be University in Visakhapatnam, India. Dr Sagi has worked in Japan and published several academic articles on the Japanese decision-making process (see the list of her publications here).

Grégoire Aubin, Vignon Gnahoui, and Badaoui Salah interviewed Dr Sagi Srilalitha Girija Kumari, who shed interesting light on meetings and decision-making processes in Japan. Dr Sagi is Associate Professor & Chairperson Executive Education & MDPs, Department of International Business, GITAM School of Business, GITAM Deemed to be University in Visakhapatnam, India. Dr Sagi has worked in Japan and published several academic articles on the Japanese decision-making process (see the list of her publications here).

Thank you to Dr. Sagi, the students, and the School of Economic Warfare for sharing these insights, which can be extremely useful for those working with Japanese partners.

Note – In the transcript below, questions and reactions in italics are those of the student team.

***

In the case we examined, Christine [name changed], a member of the executive committee of her company, went on a mission to Tokyo to meet with a Japanese partner. She was tasked with sharing strategic directions and making proposals to the Japanese team. When she spoke at the first meeting, the Japanese executives remained impassive and silent, and the Japanese director concluded the meeting without reacting. At a second meeting a month later, she proposed solutions regarding the new directions again, believing she had poorly presented her ideas at the first meeting, but the same scenario unfolded. Feeling isolated and misunderstood, she returned to France prematurely, just three months after her arrival.

Today, Christine realizes how crucial it was to prepare for her integration on an intercultural level. For example, the concept of a meeting as a space for discussion where everyone can express their ideas and debate is not readily apparent to the Japanese, isn’t it?

Dr Sagi – Let me share an anecdote. When I worked in Japan, we went on a mountain outing once a month on Sundays. Even for a simple Sunday hike, I received three pages of instructions two days beforehand. These instructions detailed the types of plants we would encounter, the locations of the toilets, the breaks, and so on. This illustrates how everything must be anticipated. Japanese culture values planning and predictability, which is a key dimension when seeking to integrate into a team and make proposals.

In our case, what should Christine have known to better prepare herself?

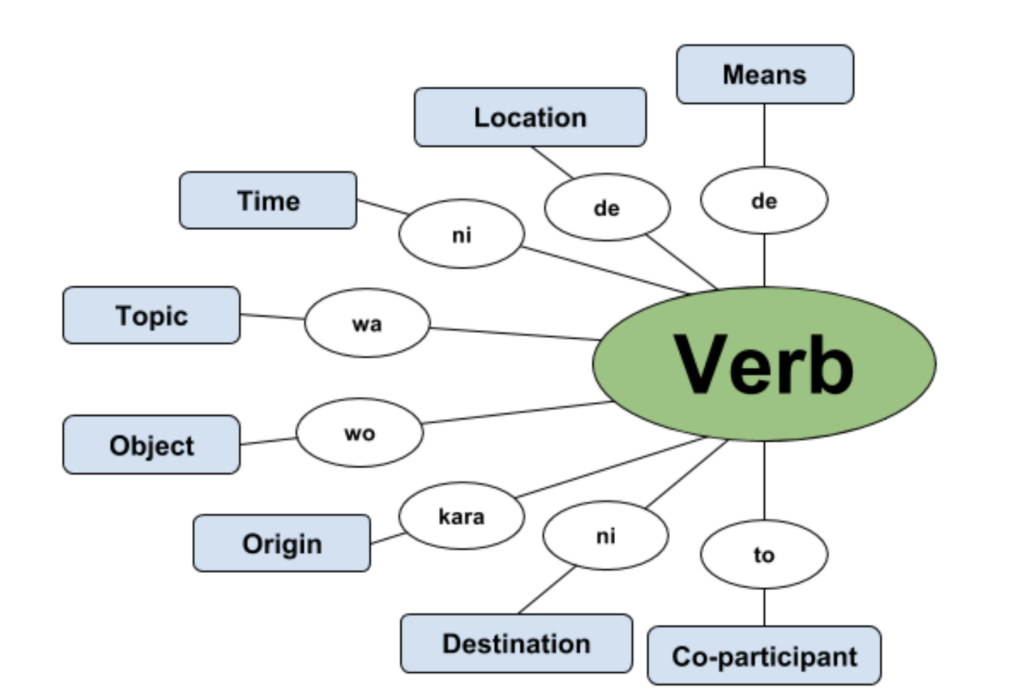

Dr Sagi – The Japanese are very procedural. This sense of preparation also applies within companies. They want neither surprises nor errors. Decisions must follow standard procedures, and this applies to all actions, including organizational decisions. Here, we must mention a Japanese concept, nemawashi. The term comes from gardening—it means “preparing the ground around the roots before transplanting a tree.” In an organizational context, it means that before making a decision, you must consult with the people concerned, understand their potential objections, and gradually lead them to accept the change. If a decision is made without prior notice, it causes a shock. And if you do not get collective agreement, the decision is perceived as a failure. Therefore, you must prepare the ground and circulate the information several days beforehand. This helps preserve cohesion and avoid open conflicts.

Like a kind of pre-negotiation?

Dr Sagi – Exactly. This can involve informal exchanges in the corridors or over coffee. For example, if I want to invite someone from India to a meeting, I will first subtly discuss it with a few colleagues before making it official. A decision should never come out of nowhere. This helps maintain harmony.

And if there is disagreement?

Dr Sagi – If a decision is not well received, it is perceived as a loss of face. To avoid this, they do their “homework.”

Their homework?

Dr Sagi – Yes, a kind of preparatory work. Keep the gardening analogy: doing nemawashi is like preparing a bonsai to be moved. Before removing it, you water around the roots and gently detach them. Only then do you uproot it. It’s the same with decisions: you must first identify the people likely to oppose, understand their concerns, and meet with them beforehand. This helps preserve face and avoid direct opposition.

So, even if the decision does not change, the effort of consultation is appreciated?

Dr Sagi – Yes. Even if the final decision remains the same, consulting shows respect. In Japanese culture, a decision announced abruptly by email at 7 a.m. would be very poorly received. They would wonder, “Why this sudden change? We should have been warned.” In Western culture, a leader can decide alone, and collaborators will follow or protest. In Japan, this is not the case. They will not openly say, “I disagree.” But they will disengage. They will implicitly say, “I am not involved.”

So Christine encountered a form of silent disobedience?

Dr Sagi – Exactly. The Japanese do not confront directly, but there is dissatisfaction. This manifests as withdrawal: they no longer talk to you or smile at you. A small alienation sets in. They oppose discreetly. They will not say, “I disagree,” but they will disengage, creating silence and distance. Ultimately, this can lead to leaving the company. This is exactly what the Frenchwoman in your case study experienced. To integrate into Japan, you must first understand what the Japanese do not like and then adapt your way of doing things.

A Culture of “Zero Surprise”

So, everything must be explained beforehand?

Dr Sagi – Yes. It is a culture of “zero surprise.” If you want me to participate in your decision, I must be informed beforehand. Even for something as simple as a change in routine or a louder voice in the office, we must warn others. For example, if I know that tomorrow I will have an online meeting with foreign students and that I risk speaking loudly, I must 1) close the glass door, but that is not enough, 2) warn my colleagues the day before by email: “Tomorrow I will have a meeting with foreign students. I will speak once or twice. Thank you for your patience.” Everything that deviates from the usual framework must be announced, explained, and shared. Otherwise, people wonder, “Why are you doing this?”

Even the smallest gestures?

Dr Sagi – Let’s say you are in an elevator. You have two papers, I have a small bag, and a Japanese person enters with a large suitcase. The first thing they will say is, “Sorry, sorry.” They apologize immediately, not because they have done something wrong, but because they are taking up more space than others. They will explain their presence: “I am sorry, I am carrying this bag.” Even when leaving the elevator, they will say again, “Sorry to have disturbed you.” They will never say, “I take up more space because I need space.” No, they will say, “May I ask for a little more space?” This behavior shows a very strong respect for others’ space. They do not demand or impose but ask. Even if they only take the lift up three flights of stairs, they’ll apologise, they will apologize for taking up space. It is a very marked cultural politeness.

Does nemawashi have its origins in Japanese cultural traditions?

Dr Sagi – It is a cultural mix. The roots can be found in Confucianism (respect for order, hierarchy, harmony), Shintoism (purity, respect for nature and places), and Bushidō (the ethics of the samurai: loyalty, humility, respect). Even a powerful samurai, upon entering your home, would say, “I am sorry to occupy your space.” It is not appreciated when an individual imposes themselves without warning.

The Informal Serving the Formal

And can this nemawashi process take place outside the formal framework of the company?

Dr Sagi – Yes, often it does. The most important discussions take place after working hours, at dinner or over a drink. During office hours, meetings must remain brief and operational. Strategic exchanges, on the other hand, often take place outside of these hours. We exchange openly: Do you think this method is appropriate? Is it an emerging trend? Do you have any ideas on this subject? Would you like us to make changes? Do you think this color is suitable? Or this banner? It is a way to integrate collaborators into the exchanges. This helps them not feel excluded; they are not strangers to the decision.

Like informal preparation?

Dr Sagi – Exactly. This involves a lot of face-to-face exchanges in small groups before officially making a decision. For example, if I am part of the production department and you are from international marketing, I can meet you in the cafeteria or in the corridor and start a discussion: “We are thinking about a change. Do you think we could invite an Indian colleague for an exchange?” This allusion, the beginning of an informal conversation, prepares the ground. Thus, when three days later a meeting is officially announced, you are not taken by surprise. This creates a form of harmony.

When the nemawashi process, with individual or small group discussions, takes place outside the company framework, is it to avoid encroaching on productivity?

Dr Sagi – Yes. For example, at lunchtime or in the evening. Long strategic discussions are generally not held during working hours. Between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m., everything is very structured. Meetings must be brief and efficient. But a deeper discussion about a strategy or a change of direction takes place after 5 p.m., often in a restaurant or over a drink. There, the exchanges are freer and less hierarchical, and they really allow opinions to be gauged. After 5 p.m., the setting is more informal, but in reality, it is very formal in substance. It is as if it were still at the office: we do not realize it, but major decisions are made at that time. They serve as the basis for even more important decisions.

The Japanese Art of Decision-Making

Specifically, how does the process from suggestion to validation work?

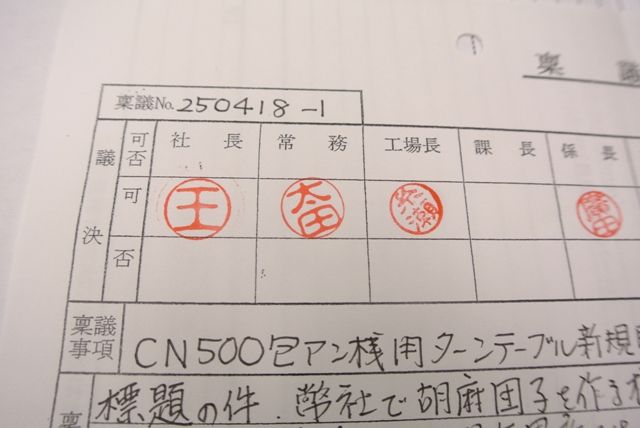

Dr Sagi – Imagine a collaborator has an idea. They discuss it with their direct supervisor, who finds it relevant. Together, they evaluate several aspects: What are the financial implications? Do we need to replace a machine? Do we need to add equipment? How would this improve speed? Would employees and customers benefit? If there is a consensus, then this idea becomes a serious suggestion. We move on to the ringi-sho: a validation document that will circulate among the decision-makers, each stamping it if they agree. The ringi-sho is thus stamped by the supervisor, who adds their comments and sends it to their own superior. This superior will, in turn, discuss it with the collaborator and their supervisor and validate or reject the suggestion. Thus, at some point—say at 3:20 p.m., when the committee is gathered—all levels will have validated the proposal. It will then be officially stamped with a red seal.

on to the ringi-sho: a validation document that will circulate among the decision-makers, each stamping it if they agree. The ringi-sho is thus stamped by the supervisor, who adds their comments and sends it to their own superior. This superior will, in turn, discuss it with the collaborator and their supervisor and validate or reject the suggestion. Thus, at some point—say at 3:20 p.m., when the committee is gathered—all levels will have validated the proposal. It will then be officially stamped with a red seal.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of this way of doing things?

Dr Sagi – One of the advantages is that everyone can use the same mechanism for submitting ideas. But the larger the company, the more cross-departmental departments and hierarchical levels (vice-presidents, directors, etc.) it has, and the longer and more crucial the process becomes. This Japanese process is collaborative but also slower because it involves multiple levels of validation.

In our case, Christine presented new proposals at the meeting. The Japanese director continued with the company’s overall strategy, and all the Japanese colleagues remained frozen and silent. We sensed a kind of discomfort.

Dr Sagi – Yes, this resembles a case of “mensu“—that is, a lack of preparation or respect for the collective framework. You are on my team, you are sitting next to me, and suddenly, you propose a new idea at the meeting without having talked to me about it beforehand? This is perceived as an unwelcome surprise. “I do not like last-minute surprises.” If you do that, it means you do not trust me. So I think, “You did not talk to me about it? So you are hiding something from me?” And this creates a trust issue.

Knowing How to Prepare and Adapt

In this case, could the director have taken the Frenchwoman aside and explained how to better present her idea?

Dr Sagi – Yes, it is a good reflex and a welcome effort, especially in an intercultural environment. In Japan, during a formal meeting, if I have nothing serious to say to you, I may not speak to you. It is not impolite; it is cultural. It does not mean that I do not respect you. It’s just that there is no subject to discuss, so I close the meeting without lingering. So, do not take it personally. You should not misinterpret the silence or lack of exchange. When people come from abroad to work in Japan, it is very useful to have an awareness program. Thus, in Christine’s case, she would have needed guidance on: How to behave in a meeting? How to present your ideas? What can be expected from a foreign executive? How to speak without shocking? How to start or conclude a meeting?

An intercultural guide, in short?

Dr Sagi – Of course. Imagine a foreigner leading a team in Japan but not knowing how to open a meeting. In their home country, they can arrive with a coffee in hand, a croissant in their mouth, and say, “Let’s go!” But in Japan, this would be perceived as disrespectful. Here, we prefer to sit calmly, take our time, and respect the forms. In Western countries like the United States, you can have a meeting standing in a corridor to save time. But in Japan, this would be unthinkable in a formal context. In Japan, making a quick decision is not a good sign. You have to take your time, sit down, and discuss. There are, therefore, a multitude of implicit cultural connections to understand. There is an unwritten rule: A foreigner who comes to work in Japan must have found out about Japanese culture beforehand. Otherwise, they will fail. Let us recall once again this implicit rule in Japan: “It is not that you cannot do something; it is that you must first inform before doing it.”

Do you have any other advice to give to Christine?

Dr Sagi – What is important is that you take notes. Even in an informal setting, writing means that you are serious, committed, and that you respect the ideas of others. Let’s say I meet you and your three colleagues. I must listen to you, ask for your opinion, and especially write it down. The Japanese interpret this as a sign of professional respect. It shows that I take our conversation seriously. Imagine I call a meeting, we exchange a lot of information, but I do not write anything down. The Japanese might think, “She came, but she is not serious.”

And to speak?

Dr Sagi – Yes, there are very precise norms for speaking in meetings. You do not interrupt someone; you wait until they have completely finished before asking a question. In other cultures (e.g., French or American), you can ask questions while someone is speaking in a fluid manner. But in Japan, interrupting is poorly perceived. To do well, you must wait until the end of a speech or formally ask for the floor in advance. In some cultures, the way you approach a subject outside of a meeting can seem out of place. “Why are you talking to me about this now? The meeting is tomorrow.” This is typically an American reaction. They may perceive this as a waste of time. Each culture has its temporal and contextual frameworks for discussing a given subject.

How to proceed then?

Dr Sagi – “Excuse me, I must talk about it.” This type of formulation is common. Open conflicts are rare. If they exist, they are often avoided or diverted. A Japanese person will not say, “This is bad.” They will rather say, “I do not think this is so good,” which, in fact, means it is very bad. The language is indirect, out of respect and to preserve harmony. In the case that interests you, imagine that Christine has three questions to ask three different people in a meeting. She should plan a slot every 10 minutes for her interventions and, to do this, send a prior message to the meeting leader (by email or otherwise) to prepare the group for her intervention. Thus, she does not surprise anyone; she respects the cultural protocol, and her intervention is well received.

Are these particularities evolving with the younger generation of 2025?

Dr Sagi – Today, the new generation is very different. They no longer want the traditional model at all. For them, it is: “I do not want to be stuck in an office. I prefer to do three small jobs, two hours each. It is my time; I distribute it as I wish.” Young Japanese no longer believe in lifelong employment or long-term stability. They seek high salaries, short missions, and creative activities (web articles, design, animation, etc.). They prefer to say, “I work three days, four hours a day. The rest of the time, I play, I learn music, etc.” This new way of functioning calls into question the traditional system. Japan, for example, is relocating its factories because the younger generation refuses to work longer, especially in the industry.

And in this context, is nemawashi still relevant today?

Dr Sagi – Yes, even with the new generation. Because they want to be informed, understand, and participate in decisions. They do not want everything to come from above. They want dialogue and meaning.

Thank you very much, Dr Sagi, for taking the time to provide us with these valuable insights.

Quelques suggestions de lecture:

- The surprise effect, or the enemy of cross-cultural communication

- The French and the demon of theory: 3 stories

- When details are monumental – 4 cross-cultural edifying stories

- In the Land of Equality – A Frenchwoman Shares Her Finnish Experience

- Intercultural meetings: 10 good practices to reduce misunderstandings

- Cross-cultural Turbulence at Air France-KLM: employees share their experiences

Derniers commentaires